(Graphs courtesy of Oregon Office of Economic Analysis)

A year ago, economists were warning about the high probability of recession. Historically, inflationary economic booms have not ended well. However, the past year has gone better than economists could have hoped for. Inflation is at or near the Federal Reserve’s target. The labor market has rebalanced and is no longer overheated. Importantly, underlying economic growth, as measured by real GDP and consumer spending, remains strong.

Looking ahead, expectations are for the economy to remain cyclically strong with low unemployment and household income growth outpacing inflation. And while the Fed will adjust policy based on the state of the economy, threading the needle may be challenging this year. Should the Fed cut rates too quickly or deeply, it may spur stronger economic growth and a rebound in inflation. However, should the Fed not cut rates quickly or deeply enough, it would leave interest rates too high for the economy and could choke off growth.

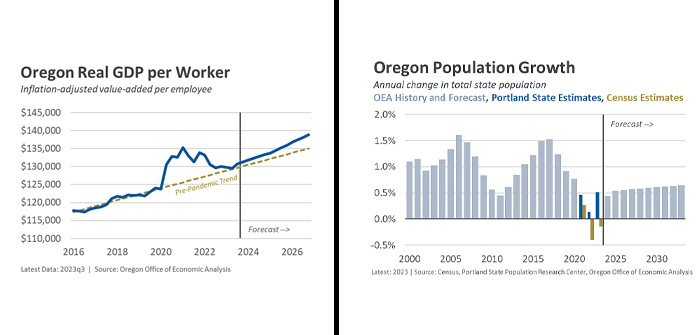

The key drivers of the regional economy are the number of workers, and how productive each worker is. In the decade ahead, labor and capital are expected to be on different, structural trends, providing crosscurrents for the economy.

First, the good news is business investment and productivity are expected to be stronger in the coming years than they have been in the recent past. The start-up boom means there are many more new businesses, which tend to drive innovation. New firms are generally better at bringing new products, services, and efficiencies to market. Since 2019, the number of businesses in Oregon has increased 25 percent, while Central Oregon’s gains are even greater at 32 percent in Crook County and 36 percent in Deschutes County. From a big-picture perspective, it is not about whether any given new business succeeds or fails, but with so many more new firms, the overall probability that some of them will hit it big and drive economic growth is higher.

Additionally, productivity is expected to increase due to private and public investment in business expansions, infrastructure, housing, and industrial policies. In the near term, this activity will boost growth, and increase the competition for construction workers, but in the long run, it will provide productivity gains for the entire economy. In particular, the CHIPS and Science Act is expected to see tens of billions of dollars of semiconductor and related investment in Oregon. This supports thousands of construction jobs in the coming years and creates thousands more new industry jobs once the projects are complete.

Now, the bad news is net labor gains are expected to be minimal in the years ahead. The labor market is cyclical strong, meaning more working-age adults have a job today than at any point in the past 20 years. The labor market is also structurally tight due to the increased number of retirements as the Baby Boomers reach their 60s and 70s, and due to the slowdown, and even losses, in migration in recent years. The end result is good news for workers; and ongoing challenges for local firms to hire in the years ahead.

Our office’s baseline population forecast is for a modest rebound in migration in the years ahead. Over the next decade, annual population gains are expected to be just 0.6 percent. This is a far cry from the 1-2 percent gains seen in recent cycles. And while Central Oregon population growth will be above the statewide figures, the region is not entirely immune to the broader trends that include increased deaths with a growing older population, the declining birthrate, and some structural factors slowing migration like high housing costs.

Even as the baseline population forecast calls for some growth, Oregon has to be open to the possibility that it may not materialize. The pandemic may ultimately be a breaking point, where future trends do not look like previous trends. Our office has developed a Zero Migration alternative scenario that models the economic and revenue impacts should migration not rebound. The bottom line is this. In such a scenario, Oregon’s economy, income, consumer spending, and public revenues would not crater. Rather, they would all be on a slower growth trajectory. Keep in mind that due to inflation, wage gains, and rising asset markets, income and spending will increase among Oregonians. The issue would be the number of Oregonians would not grow as expected, leaving a slowly declining population as deaths outnumber births statewide. Such changes are relatively small in any given year, particularly as you compare the slow baseline to the Zero Migration scenario, but they do accumulate over time leaving Oregon noticeably different a decade from now than is expected in the baseline outlook.

To the extent that housing affordability is a key factor in migration decisions, in addition to any other number of issues and topics, increased housing production would provide three key benefits. First, it would boost near-term economic growth. Second, it would improve household finances, allowing more of our neighbors to financially make ends meet. Third it would likely revive some of the lost migration trends, boosting the workforce of tomorrow.

Ultimately, the economic outlook comes back to that combination of labor and capital. Encouragingly, Central Oregon has seen strong productivity gains in the most recently available data. At the county level, from 2019 to 2022, real GDP per worker increased about two percent in the typical U.S. county. The gains were four percent in Jefferson County, nine percent in Deschutes County, and 19 percent in Crook County. Looking forward, above-average productivity gains are likely to be the key driver of the local and regional economy, especially if population growth remains slow.