Can you remember an employee who, just after being passed over for promotion, died (figuratively, of course) on the job? Or do you recall a new employee who joined the company full of enthusiasm and energy but became a real disappointment when the smoke settled? Or, closer to home, can you recall feelings of being emotionally wasted, of becoming more callous toward others, or of feeling personally ineffective on the job? If you can answer yes to any of these questions, you’ve probably had personal experience with employee burnout.

Unfortunately, if you’ve had such an experience, you are not alone. Increasing numbers of once qualified, energetic and productive employees are becoming victims of burnout. And unless organizations act now, it is likely that these numbers will continue to increase. Because burnout is so detrimental to organizations as well as individuals, it is critical for employers to move now to prevent employee burn-out. In this article we describe strategies that human resources managers can use to help prevent employee burnout in their organizations. First, however, it would be useful to examine employee burnout more closely.

What Is Employee Burnout?

Employee burnout can be thought of as a psychological process — a series of attitudinal and emotional reactions — that an employee goes through as a result of job-related and personal experiences. Often the first sign of burnout is a feeling of being emotionally exhausted from one’s work. When asked to describe how she or he feels, such an employee might mention feeling drained or used up, at the end of the rope and physically fatigued. Waking up in the morning may be accompanied by a feeling of dread at the thought of having to put in another day on the job. For someone who was once enthusiastic about a job and idealistic about what could be accomplished, feelings of emotional exhaustion may come somewhat unexpectedly, but the boss or co-workers may see the person’s emotional exhaustion as a natural response to working too hard. In turn, their natural response is to tell the victim to “Take it easy,” or to say “You need a vacation.”

Instead of doing either of these things (neither of which would provide permanent relief anyway), the victim does what many employees in similar situations have done — she or he copes by depersonalizing relationships with the boss and co-workers. She or he develops a detached air, becomes cynical of relationships with others and feels callous toward others and the organization. Managers who become burnout victims are especially harmful to organizations because such managers create a ripple effect, spreading burnout to their subordinates. Unfortunately for the friends and family of an employee who has reached this stage, the cynical and uncaring attitudes that develop toward co-workers, boss, or subordinates may also be directed at nonwork contacts, having a negative effect on all of the person’s social interactions.

In addition to emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, a third and final aspect of burnout is a feeling of low personal accomplishment. Many individuals begin their careers with expectations that they will be able to make great contributions to their employer and society. After a year or two on the job, they begin to realize they are not living up to these expectations. Many systemic reasons may contribute to the gap that exists between a new employee’s goals and the veteran’s accomplishments, including (1) unrealistically high expectations because of a lack of exposure to the job during training, (2) constraints placed on the worker by organizational policies and procedures, (3) inadequate resources to perform one’s job, (4) co-workers who are frequently uncooperative and occasionally rebellious and (5) a lack of feedback about one’s successes.

These and other characteristics almost guarantee that employees will be frustrated in their attempts to reach their goals, yet these employees may not recognize the organization’s role in causing their frustration. Instead they may feel personally responsible and think of themselves as failures. When combined with emotional exhaustion, feelings of low personal accomplishment may reduce motivation to a point where performance is in fact impaired and that, in turn, leads to further failure.

Conditions That Cause Employee Burnout

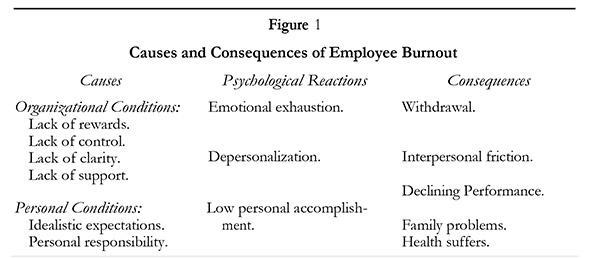

Although we have already alluded to a few conditions that cause employee burnout, it would be useful to spell them out more specifically. As shown in Figure 1, two types of conditions — organizational and personal — may trigger employee burnout. Organizational conditions that can potentially cause burnout include these: (1) a lack of rewards; (2) excessive and outdated policies and procedures, work-paced jobs and close supervision — all of which undermine an employee’s “feeling of control”; (3) a lack of clear-cut expectations and job responsibilities, combined with conflict — both of which prevent an employee from being productive; and (4) the lack of support groups or cohesive work groups, which, in turn, prevent an employee from acquiring information needed to cope with the other three conditions. Note that these four organizational conditions may be behind employee burnout, but several personal characteristics usually interact with these organizational conditions to actually cause employee burnout.

Such personal characteristics include the following:

Idealistic expectations. The employee has unrealistic expectations about how the organization will work, and these, when combined with actual organizational experience, produce “reality shock.” For example, the employee might expect rewards for good work, the chance to influence decisions affecting the job, friendly and understanding co-workers and supervisors, a clear understanding about what’s expected and adequate resources (including time and money) to get the job done.

Idealistic job and career goals. Organizational conditions that interfere with performance are bothersome only to employees who want to attain high levels of performance. An employee who thinks it is possible to do everything becomes a natural target of burnout. Employees in mid-career crisis reflect burnout reactions, especially feelings of low personal accomplishment. Although many of these employees may have been doing well by others’ standards, by their own standards (for example, a goal of becoming president of the company by age 50) they may regard themselves as failures.

Personal responsibility for low personal accomplishment. Employees with feelings of low personal accomplishment, those who feel most personally responsible for their own failure, experience the most burnout. Essentially, the employees who care the most can get burned (out) the most.

Consequences of Employee Burnout — To the Organization, To the Individual

A legitimate question at this point may be, “Okay, so some people experience burn-out. Organizations aren’t perfect and never will be. And even if they could do something, what’s the big deal about burnout7” The big deal is that the organization as well as the individual suffers many severe consequences as a result of employee burnout. The first paragraph of this article suggested a few. Others include the following:

Withdrawal behaviors develop. Employees want to avoid what discomforts them, and those organizational conditions that can cause burnout are certainly discomforting. Under these circumstances a logical reaction is to withdraw — leave work early, arrive at work late, take long breaks and stay away from the workplace as much as possible.

Interpersonal friction results. As employees begin feeling cynical and callous toward others, small differences lead to monumental arguments, work assignments begin to seem like insurmountable challenges and friends begin to look like foes.

Performance declines. As a subtle result of burnout, the quantity of an employee’s performance may not diminish but the quality may. Consider the job of an intake interviewer in a legal aid office as an example.

For the organization, the intake interview serves as a screening device through which all potential clients must pass. During the interview, specific information about the nature and details of a case must be assessed and an evaluation of the “appropriateness” of the case for the office must be made. Because as many as 40 intake interviews may be conducted each day, it is important that the interviewer work as efficiently as possible. Here the major index of efficiency is the number of forms accurately filled out for further processing. Thus the interviewer’s attention must be focused on gathering information needed by the organization for its evaluation. To the extent that time is spent in talking about problems that are not relevant for these forms or this procedure, efficiency decreases.

Now consider the client’s perspective. Upon arriving for an interview, the client is likely to be fuming inside at injustices that have been suffered and the retaliations hoped for. The client does not think in terms of the precise statutes that pertain to the problem nor of the essential details that make her or his case worthy of attention. Rather, the client is concerned with family problems arising from the situation.

The primary concern is that emotional and physical life return to normal and that the law seems to offer a solution. For the client, the intake interview may be the first chance to explain the problems. From the client’s perspective, an interviewer who lends a sympathetic ear is doing a good job.

How will the interviewer handle this situation? Typically, the person conducting the interview is a relatively recent graduate of law school with little or no clinical experience. The only guidance that he or she has received are generalities about the professional approach to analyzing cases. Professional training has emphasized the supremacy of objectivity. But clearly, an objective, analytic attitude combined with the pressure to efficiently fill out forms does not lead to the sympathetic ear the client is looking for. Because of these differing expectations about the interview the client and the interviewer perceive each other as obstacles. The objective interviewer appears unconcerned, and the client becomes frustrated. The emotionally involved client becomes an obstacle to detached efficiency, frustrating the interviewer.

Whether or not open hostility erupts, the participants are aware of their antagonistic relationship.

One way for the interviewer to cope with this situation is to develop a limited set of case types and then focus on determining which type a client fits into. Once a case has been “typed,” the unique nuances of the case can be ignored. Processing of the case then proceeds as it does for all other cases of that type. This method of coping can lead an interviewer to adopt a rigid line of questioning governed by the papers to be filled out rather than by the clients and their concerns. Although the interviewer will probably recognize that this strategy is less than optimal, it may be the only feasible way to deal with the myriad complexities and details of each case. Under these circumstances, the client perceives the interviewer as just another petty bureaucrat who is more concerned with paper than with people.

Family life suffers. Just as burnout leads to behaviors that have a negative impact on the quality of one’s work life, it can also lead to behaviors that cause a deterioration of the quality of home life. In a recent study by Susan Jackson and Christina Maslach, burnout was assessed in 142 married, male police officers. Their wives were asked, independently, to describe how these officers behaved when interacting with their families at home. Emotionally exhausted officers were described by their wives as coming home tense, anxious, upset and angry, and as complaining about the problems they faced at work. These officers were also more withdrawn at home — preferring to be left alone, instead of sharing time with their families. The wives’ reports also revealed that officers who had developed negative attitudes toward the people they dealt with also had fewer close friends.

Finally, burnout may eventually lead to health-related problems. In the study of police families described above, burnout victims were more likely to suffer from insomnia and to use medications of various kinds. The officers also reported using alcohol as a way of coping with their burnout as did female nurses in an unpublished study, suggesting that using alcohol to cope with burnout is not unique to police officers or to males.

Preventing Employee Burnout

Organizations can do many things to prevent employee burnout. On the basis of our employee burnout model in Figure 1, organizations can change any one or all of the organizational conditions causing burnout. For example, supervisors could be trained to provide more contingent (based on performance) rewards to employees, thus eliminating the comment, “If you don’t hear anything, you must be doing okay.” Organizations could redesign jobs to enable employees to have more control over their work. Compensation could be more closely related to the level of employee performance. Although such programs could be successfully implemented by human resources managers, the cost and time required by them may be greater than that for the three programs described below — that is, anticipatory socialization programs, participative management programs, and/or feedback programs. The first of these is appropriate for new employees and the other two for current employees. Because of the relatively low cost of these programs, many organizations are already moving to adopting them. Thus the discussion here will provide arguments to persuade others to adopt them.

Anticipatory Socialization Programs

In Reality Shock: Why Nurses Leave Nursing, Marlene Kramer argues that a major source of burnout in the nursing profession is the gap between the expectations that nurses have when they begin their first job and the realities that they actually find. Nurses and others who enter human services professions are often strongly motivated by a concern for humanity and a desire to help people. When they start their first job, they anticipate being able to make visible improvements in other peoples’ lives and although they may not realize it, they also expect their contributions to be recognized as valuable. As any seasoned human services worker has discovered, the lofty expectations and goals they had as a novice were unrealistic. From the beginning they were doomed to failure if success meant achieving those naive goals. Similar findings were reported by Edgar Schein in his study of employees across many different organizations.

What can be done to prevent the devastating shock that occurs as a result of the discrepancy between naive ideals and reality? Kramer presents convincing evidence that anticipatory socialization programs can help decrease the magnitude of reality shock and its consequences. The philosophy underlying anticipatory socialization programs is that reality shock should be experienced before an individual begins his or her first full-time job. Furthermore, the reality shock should be experienced in a context that permits and encourages the development of constructive strategies for coping with the unexpected reality one faces. Throughout such a program, ideals are purposely challenged, and conflicts — such as the difference between the way things should be done based on personal or professional standards and the way things actually are done — get exposed. Individuals are then taught how to survive within the existing system without compromising their standards.

Kramer has demonstrated that anticipatory socialization can be an effective method for decreasing the severity of the reality shock experience on the job. This, in turn, decreases turnover rates and absenteeism. Because Kramei’s anticipatory socialization program can serve as a model for any occupational group in any type of organization, it is outlined briefly below.

Phase 1. The purpose of the program’s first phase is to produce a mild form of the reality shock that an uninitiated worker might experience on the job. This is accomplished by presenting examples of real, on-the-job incidents that have been experienced by others.

Phase 2. New employees are exposed to the negative aspects of policies and practices that characterize most organizations. During phase 2, new employees are encouraged to actively think about possible solutions for improving the situation. By thinking about the problems and trying to devise solutions, the new employees come to appreciate and better understand the reasons why certain imperfect conditions exist.

Phase 3. Phases 1 and 2 focus on the employee’s own expectations of how he or she should behave, but phase 3 of Kramei’s program aims to teach the employees what others expect. For example, the nature of the nurse-physician relationship is presented by a panel of physicians and nurses. Similarly, a panel of head nurses, supervisors and administrators expose the novice to the expectations held by their immediate superiors. Another important aspect of phase 3 is a panel discussion by recent nursing graduates who describe what they are, and are not, able to accomplish on their jobs — thereby providing a realistic baseline against which the program participants can evaluate their own future success and failure.

Phase 4. The final phase of Kramer’s program is to teach theories and techniques of conflict resolution and negotiation. The intention of this phase is to teach skills that can aid the nurse in her or his role as an agent for change. These skills give the novice the option, in the future, of working toward changing those parts of a system that present conflict to something that is acceptable.

In summary, these are the pertinent features of anticipatory socialization. First of all, its major goals are to give new employees a realistic picture of the jobs they are about to enter and to provide skills for coping effectively with the difficulties they will face. Because the jobs are not ideal, negative aspects are exposed. While this exposure is not intended to dissuade people from starting a job, it may, of course, do so. Therefore, employers may be reluctant to conduct such programs for fear of losing potential future employees. On the other hand, the employer may conduct anticipatory socialization programs but downplay the negative aspects of the organization, thereby defeating the purpose of narrowing the gap between expectations and reality. Anticipatory socialization programs, however, are most beneficial when they convey the negative as well as the positive aspects of the job. A second import ant feature of anticipatory socialization programs: While they are aimed at burnout prevention, they are most appropriate for new employees. Exposing a five-year veteran to such a program would probably do little to prevent burnout.

A third important feature of anticipatory socialization programs: They are not designed to change reality, but merely to expose it in hopes that forewarning will lead to better preparation. As such, anticipatory socialization programs are likely to be useful for decreasing the frustrations that occur during the first two or three years. However, simply being prepared for the negative aspects of one’s job does not guarantee that long-term exposure to that job will not lead to burnout. Changes in the job itself or other organizational conditions may also be needed.

Increasing Participation in Decision Making

The importance of being able to control, or at least to predict future outcomes, is well-recognized by organizational researchers. Having opportunities to make one’s own choices and the freedom and ability to influence events in ones surroundings can be intrinsically motivating and highly rewarding. When opportunities for control are absent and people feel trapped in an environment that is neither controllable nor predictable, both their psychological and physical health are likely to suffer.

In most organizations, employees are and feel controlled by organizational rules, policies and procedures. Often these rules and procedures have their roots in an earlier era of the organization and are no longer as appropriate as they once were. Nevertheless, they are enforced until new rules are developed. Then, too, frequently new rules are created by people in the highest levels of the organization, and then imposed upon those at the lower levels. Sometimes the new rules are an improvement over the old rules; other times they are not. Regardless of whether the new rules or procedures are an improvement, lower-level employees are likely to perceive them as another organizational event over which they have had no control.

Fortunately, recent studies of burnout suggest that increasing employees’ participation in the decision-making process and thus increasing their control can be an effective way to prevent burnout. In addition to increasing employee’s feelings of control, participation in decision making may help prevent burnout by clarifying role expectations and giving employees an opportunity to reduce some of the role conflicts they experience. The level of role ambiguity (lack of clarity) and role conflict that people experience are strongly related to burnout. In particular, a high level of role ambiguity leads to emotional exhaustion and feelings of low accomplishment. Role conflict causes emotional exhaustion also, as well as the development of cynical attitudes towards other employees.

Besides giving workers a feeling of control, participation in decision making gives them the power to remove obstacles to effective performance, thereby reducing frustration and strain. One way in which employees can use their increased power is to persuade others to change expectations for the employees’ behavior that conflict with the employees’ own views. Through the repeated interchanges required by participative decision making, organization members can also gain a better understanding of the demands and constraints faced by others. When the conflicts other people face become clear — perhaps for the first time — negotiation over which expectations should be changed to reduce inherent conflicts is likely to occur. Another important consequence of the increased communication that results from participative decision making is that people become less isolated from their co-workers and supervisors. Through their discussions, employees learn more about others’ formal and informal expectations. They also learn about the organization’s formal and informal policies and procedures. This information can help reduce feelings of role ambiguity. It also makes it easier for the person to perform his or her job effectively.

In addition to preventing burnout by reducing role conflict and ambiguity, participation in decision making helps prevent burnout by encouraging the development of a social support network among coworkers. Recent studies have found that social support networks help people cope effectively with the burnout they experience on the job. Among employees, one of the most important functions of a social support network is that it can assure the worker that he or she is not the only one who is experiencing difficulties on the job.

Making Increased Participation Work

While participative decision making appears to be a very promising strategy for keeping burnout to a minimum, organizations that plan to use it should be aware of a number of factors that can determine whether increasing participation is likely to be effective or to backfire. Among the most difficult issues in setting up a participative procedure is specifying the types of decisions in which employees will be allowed to participate. These two guidelines should be followed when making this decision: (1) An employee’s input is most valuable when the decisions involved will have a direct impact on his or her day-to-day activities; (2) Asking employees to provide input into a decision and then ignoring their advice is worse than never having asked their opinions.

Most employees recognize that there are some decisions for which they are unprepared to provide meaningful input because they do not have all of the relevant information. However, most employees do consider themselves to be experts at their own particular jobs and in the workings of their own particular units. By necessity, people in other jobs and in other departments in the organization are less in tune with the factors that affect how well one is able to perform his or her job. Therefore, to have such people making decisions about procedures and policies that will affect one’s own job creates frustration and a sense of lack of control. By giving employees the opportunity to provide input into decisions that affect them directly, supervisors and managers will find that better quality decisions are made because the unintended, negative side effects of a particular decision are more likely to have been foreseen by the workers. In addition, employees will have more positive attitudes toward implementing decisions that they helped make.

Increasing Feedback about Performance

A final job-related change that organizations concerned about burnout should consider is increasing the amount of feedback that workers receive about their job performance. In many organizations jobs are structured so that the employee seldom hears when things go right, but always hears when things go wrong. This is especially true in jobs where the main service the employee provides is advising people about how to solve their problems. For example, in human services organizations, there is a built-in bias that prevents employees from receiving positive feedback for a job well done. However, this is true for almost any organization. Therefore, organizations need to make a conscious effort to devise ways of obtaining such feedback for employees.

One such method in a human services organization is to ask clients to indicate how satisfied they are with the service they received using a Client Feedback Survey. When client feedback surveys are conducted on a regular basis, they not only provide feedback about how well the service provider is currently performing, they also give the employee information about whether his or her performance has improved or declined.

Co-workers are also a potential source of feedback about how well employees are doing on their jobs. Just as an organization might ask clients to complete a feedback survey, co-workers can be asked to make evaluations of each other, assuming they are able to observe each other’s performance on the job. Co-worker evaluations have an advantage in that they are being made by a person who is fully aware of the constraints placed on employees by the organization. Whereas clients will tend to evaluate the service they received against an ideal standard, the evaluations of co-workers will be based on an understanding of professional ethics and practices and organizational realities.

Finally, subordinate feedback is a great way for supervisors and managers to find out how well they are doing. Because we all tend to gradually adapt to and get comfortable in the conditions in which we find ourselves, we forget to ascertain how others feel we’re doing. Because managers are responsible for others, it is imperative for them to find out what their subordinates think of them. The employees are first to know if the boss is becoming callous. Because employees are usually reluctant to give the boss bad news, the personnel department can play a critical organizational role by conducting surveys and feeding the results back to the managers. These survey results can also be used to help spot areas of conflict or ambiguity or particularly irksome rules and procedures. The personnel department can also be effective in helping to detect employee burnout levels by surveying employees with a survey specifically designed to measure burnout.

Conclusions

Employee burnout has some extremely serious consequences for employees and employers. Fortunately there are a number of things that the personnel department can do — such as implementing participatory management programs like quality circles or conducting organizational surveys — to help prevent employee burnout. However, rather than assume that one cure exists for all situations, we should assume that each organization is somewhat unique, and this uniqueness must be taken into account when potential burnout prevention programs are being considered. For example, if employee opinions are already actively solicited before most major decisions are made, increasing participation in decision making is unlikely to affect future burnout levels.

Not only is it prudent for organizations to recognize the need to be cautious in selecting an intervention strategy, it is prudent for them to accept the possibility that the particular intervention they choose may not be effective. Therefore, organizations should evaluate the effects of any intervention they implement.

SUSAN E. JACKSON is a faculty member of the department of psychology at the University of Maryland-College Park. She began studying burnout several years ago while at the University of California-Berkeley, where she received her M.A. and Ph.D., and where she participated in the development of the Maslach Burnout Inventory, of which she is a coauthor. Her articles on stress and burnout have appeared as chapters in edited volumes, as well as in the Journal of Occupational Behavior, the Journal of Applied Psychology and Psychology Today.

RANDALL S. SCHULER is an associate professor at the Graduate School of Business, New York University. His interests are stress, time management, staffing and human resources management. He is the author of a textbook, Personnel and Human Resources Management (West Publishing Co., 1981), and co-author of Managing Job Stress (Little, Brown & Co., 1981). In addition, he has contributed many chapters to various books, including Current and Future Perspectives on Stress in Personnel Management, edited by Kendrith M. Rowland and Gerry R. Farris (Allyn & Bacon, Inc., 1982).